A few days ago I received an email from a friend suggesting that we cover more basic astronomy topics for newbies, as well as suggest objects that can be seen from a light polluted sky for those not able to get to a dark sky site. This got me thinking about my bias to talk about what you can see from a dark sky site since I live in one, as well as my presupposition that most folks reading an astronomy blog are already familiar with astronomy basics. Thanks, Sheila, for reminding me that there are newbies eager to learn more about the basics, and that observing from your light polluted backyard is better than not observing at all! With this in mind, moving forward we will broaden the scope of the topics we cover here on Astro Daily.

Today I’ll talk about observing from your light polluted backyard, with a few astronomy basics thrown in. One of my favorite objects to observe is not a planet or a star, but the International Space Station (ISS). For me, there’s something magical about watching that bright little light traversing the sky and knowing that there are people in that bright little light, working on a science experiment, or eating a meal, perhaps holding their favorite object from home, or maybe settled in for their “night’s” sleep. What would it be like, I wonder, to experience sunrise every hour-and-a-half? That really changes the definition of pulling an all-nighter…

I enjoy observing the ISS so much, that it’s the first topic I wrote about here on Astro Daily. I’ve photographed thirty-four ISS passes in the past five years and observed many more: from the wee hours of the morning to way past my bedtime; throughout all seasons whether clear, cloudy or snowy; and from my own backyard to one of my favorite locations, the Old San Miguel Mission on Christmas Eve.

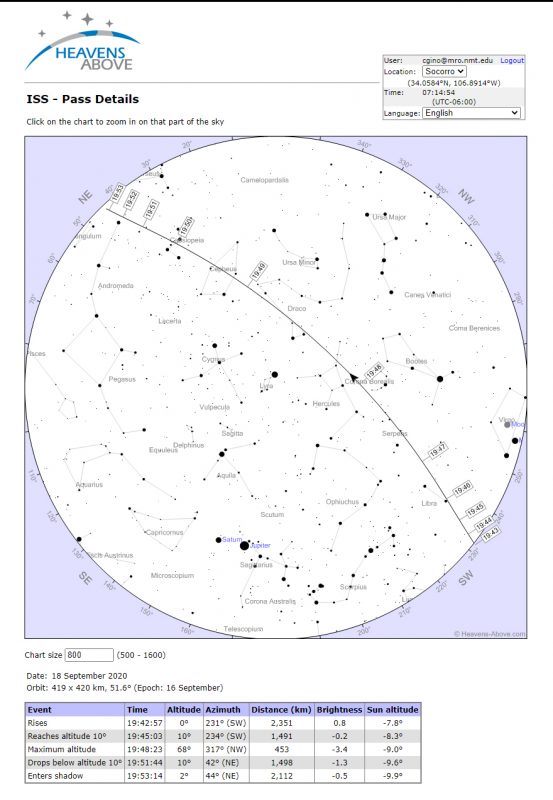

There are many websites and smartphone apps that tell you when and where to see the ISS pass overhead from your location anywhere on Earth; my favorite is the website Heavens Above, which is also available as an app. After entering your geographical location, you can retrieve information regarding ISS passes which include visibility tables and sky charts. You can also get information on various other satellite passes (such as the Starlink satellites), as well as interactive sky charts, Sun and Moon data, and much more.

Those of us in New Mexico will have a prime viewing opportunity this coming Friday, September 18. On this particular pass the ISS will rise above the horizon early in the evening (about 7:45 PM MDT), will pass high overhead (68° alt), and appear very bright (-3.4 mag) – a perfect object for light polluted backyard observing!

The skymap and visibility table above are for my location in Socorro, New Mexico, however you can generate one for your specific location. The skymap shows the actual path of the ISS in the sky, and what constellations are up at the time of the pass. Since this pass begins about a half-hour after sunset (7:09 PM MDT), we will be in civil twilight; the sky will still be a bit bright, and you can expect to see only a handful the brightest stars and planets shown on this skymap. (For a full explanation of the different kinds of twilight, please see this previous blog post.)

The visibility table lists the time when ISS will rise above the horizon and in what direction around the horizon (azimuth), the time it will be at various altitudes in its pass, and how bright (magnitude) the ISS will appear at those various altitudes. (For a discussion of altitude and azimuth please refer to this previous blog post.)

This is a good time to cover some astronomy basics. As you see above, the brightness of the ISS is referred to as its magnitude. The stellar magnitude scale is the measure of how bright an object appears to us, with brighter objects having smaller numbers, and fainter objects having larger numbers. For example, the large black dot nearly in the center of this skymap (meaning it would be about directly overhead) is Vega in the constellation Lyra, at a magnitude of 0.03. Move almost straight down from that toward the southern horizon on the map and you’ll see a slightly larger black dot, signifying the planet Jupiter. Right now, Jupiter’s magnitude is about -2.5. A bit to the east of Jupiter is the planet Saturn, currently at about magnitude 1.2 (planet magnitudes obtained from The Sky Live). To list these three objects in order of increasing brightness, we get Saturn being the dimmest at mag 1.2, Vega a bit brighter at mag 0.03, and Jupiter the brightest at mag -2.5.

As you can see from the visibility table, the ISS varies in brightness during its pass, starting dim, reaching its peak brightness of mag -3.4 when it reaches its maximum altitude in the pass, then becoming dimmer again as it nears the opposite horizon. Those of us at dark sky sites may start to see the ISS when it is 10 to 15° above the horizon, while those of you in brighter sky sites may not see it until it gets to a higher altitude.

One last thing worth pointing out is the cardinal directions shown on the skymap. North and south are where you expect them to be, but east and west are reversed from what you see on a map of the Earth. This is because skymaps are to be held over your head while you look up at them, just as you look up at the sky. Try it and see!

Hopefully I’ve inspired you to take a moment this Friday night to watch the International Space Station pass overhead. Whether you’re in your light polluted backyard or a dark sky site, and it will be your first viewing, your fiftieth (like me), or something in between, I think you will enjoy the view!

M. Colleen Gino, MRO Assistant Director of Outreach and Communications