A brave woman armed with the specialized tools of her trade sits alone in the dark and mentally prepares herself for the hunt. Her mission: to track down and identify some of the more elusive and exotic members of our solar system.

No, this is not an opening scene from Buffy the Vampire Slayer. This could be you or me, a citizen scientist, using Photoshop to animate a set of images from one of NASA’s orbiting solar observatories to hunt for comets.

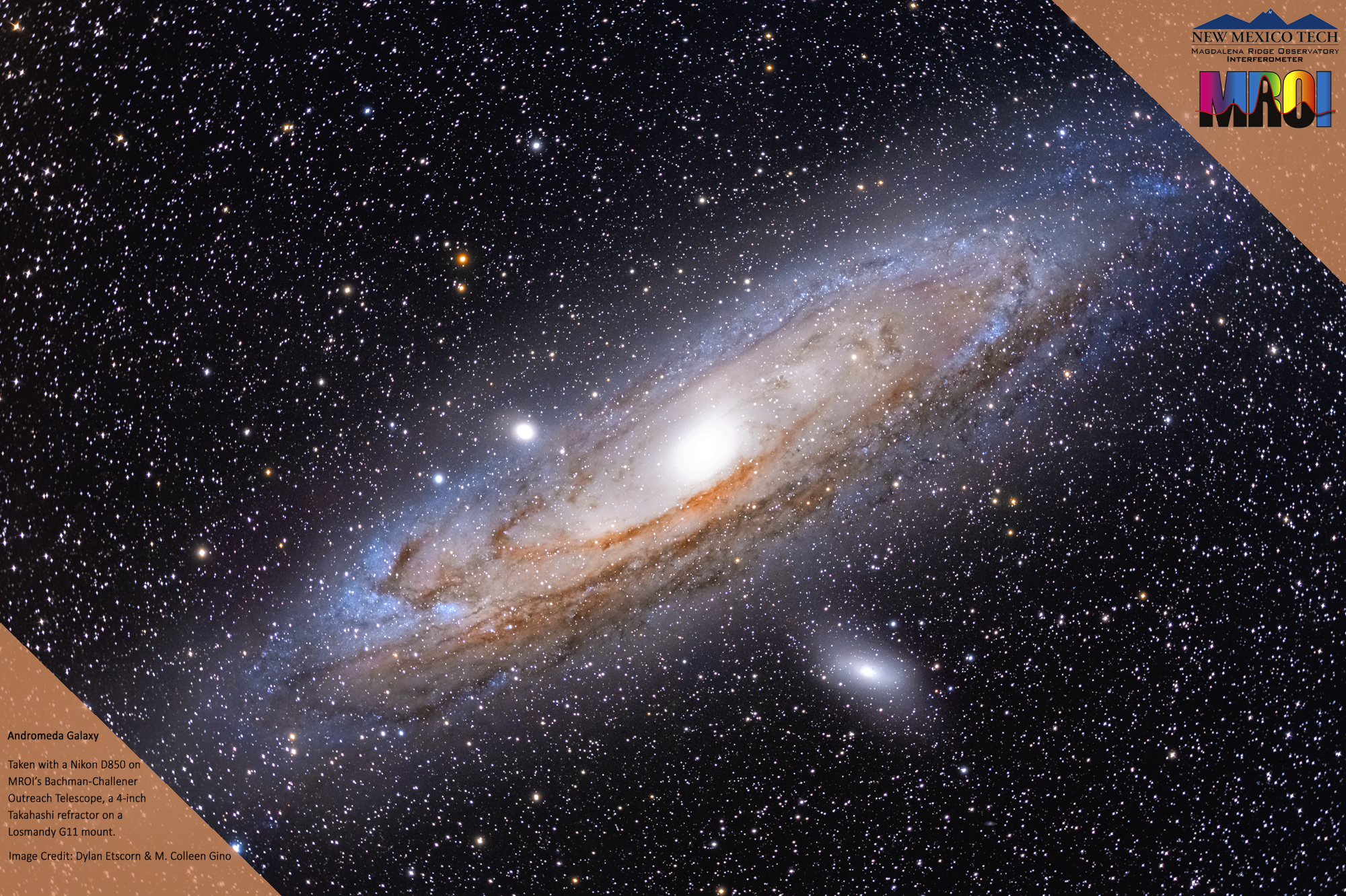

A few days back we learned about famous comet hunter Charles Messier and how his catalog of objects came about. By participating in one of NASA’s Citizen Science projects, you too can become a comet hunter even if you don’t have access to a telescope!

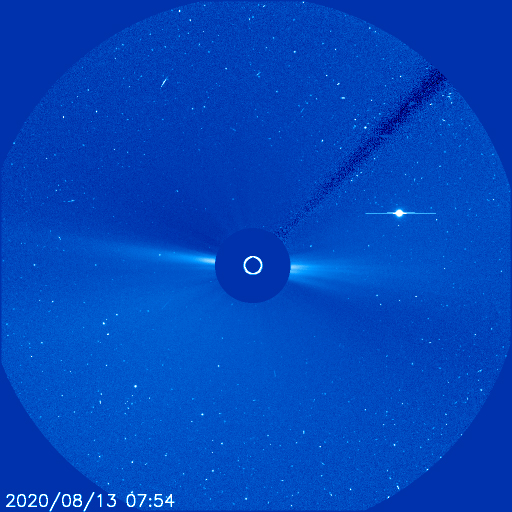

Enter NASA’s Sungrazer Project, where you can put your hunting skills to the test and hopefully discover a comet. Participants inspect images taken by the ESA/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) or NASA Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) and look for objects moving in such a way that they may be comets. To date, over 4,000 comets have been discovered in SOHO data, with the majority of those found by citizen scientists. Moreover, over 99% of SOHO’s comet discoveries have come from its LASCO coronagraph, an instrument that uses an occulting disk to block the direct light from the sun, allowing faint objects in the vicinity of the sun to be visible.

Want to get involved in the hunt? You would start by downloading a set of SOHO/LASCO still images, then animate the images using a program such as Photoshop or GIMP. When you view the animation, you’ll see a lot of moving objects, most of them stars or sometimes a planet. It’s easy to rule out the stars in the SOHO/LASCO image animation because they always move horizontally from right to left and at the same speed as one another. Planets are easily identifiable as well, since they always move horizontally either right to left or left to right, and they are generally larger and brighter than stars. Another common sight will be cosmic rays, energetic particles striking the imaging sensor. Again, these are easily identifiable because they appear in only one frame of the animation as white dots, blobs, or streaks at random locations in the field of view. To get an idea of what you’re dealing with, click on the image below to view an animation of recent SOHO/LASCO data. It’s easy to identify the stars, a planet, and a multitude of cosmic rays.

The tricky bit is finding a comet in the midst of these predictably and chaotically moving objects. You are looking for a small, faint dot moving slowly through the animation, usually toward the Sun from the lower portion of the field of view. Comets are easily distinguishable from stars and planets, as they hardly ever move horizontally through the images, and they always move with a near constant speed, size, shape, and brightness. This small, faint, slowly moving dot must appear in at least five consecutive images before being reported as a potential comet. To find out if comet hunting is for you, download a sample set of data that includes a known comet (available at the bottom of this comet hunting guide web page), and see if you can pick it out of the crowd of stars, planets, and cosmic rays.

Comets not your cuppa? No problem! You can search for exoplanets, spot protoplanetary disks around nearby stars, or process and analyze images of Jupiter. Prefer to use your own telescope? You can submit data on the brightness and position of near Earth objects, or share your Jupiter images with the JunoCam team to help them plan future photographic missions.

NASA’s citizen science projects are not limited to astronomy; you can find projects in the fields of geology, oceanography, meteorology, and more. Moreover, citizen science projects aren’t limited to NASA; use your computer’s down time to analyze radio telescope data for SETI, classify distant galaxies for Galaxy Zoo, help identify constellations in celestial maps for the Adler Planetarium, or transcribe the notebooks of the famous Harvard College Observatory women “computers” for the Smithsonian. The number of crowdsourcing projects continues to grow!

Next time you have time to kill, why not stop your Pokémon Go, close your Candy Crush, and spend some time contributing to scientific research. Below you’ll find more links to help get you started on your own hunt:

https://www.zooniverse.org/projects

https://www.scientificamerican.com/citizen-science/

http://www.cosmologyathome.org/

https://www.uahirise.org/hiwish/

https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/nora-dot-eisner/planet-hunters-tess

https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/shannon-/solar-stormwatch-ii

https://www.aavso.org/observers

http://alpo-astronomy.org/lunarupload/lunimpacts.htm

Happy Hunting!

M. Colleen Gino, MRO Assistant Director of Outreach and Communications